I ran a report to try to summarize the latest thinking on this, which is not widely known:

Elevated AFP in HBeAg-Negative Hepatitis B: Re-Evaluating Fibrosis Risk

Traditional View: AFP as a Risk Marker for Fibrosis

Historically, an elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients has been associated with more advanced liver disease. Multiple earlier studies reported that higher AFP correlates with worse liver histology. For example, one large cohort found that CHB patients with AFP >7 ng/mL had significantly higher ALT/AST and were much more likely to have advanced fibrosis (stage ≥S3) or cirrhosis on biopsy compared to those with normal AFPpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. In that study, AFP elevation emerged as an independent predictor of significant fibrosis even after adjusting for other factorspmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Another analysis of 619 CHB patients showed median AFP levels rising progressively with fibrosis stage (e.g. ~3.0 ng/mL at F0–1 up to 11.3 ng/mL at F4), with a moderate positive correlation between AFP and fibrosis extent (ρ≈0.40–0.51, p<0.001)bmcgastroenterol.biomedcentral.compmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Similarly, a FibroScan-based study in China noted that patients with AFP >8 ng/mL had higher liver stiffness readings (indicating more fibrosis) than those with lower AFP, even when ALT/AST were normalpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. In summary, the traditional consensus has been that any elevation in AFP during chronic HBV infection is a red flag – often coinciding with active inflammation, necrosis, and underlying fibrotic progressionpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Indeed, older predictive models listed “elevated AFP” (along with male sex, age, and HBeAg-negative status) as a risk factor for fibrosis in CHBacademic.oup.com. This is why doctors have historically “freaked out” and ordered cancer screenings when seeing moderately high AFP in hepatitis B patients – it was generally thought to signify something ominous, like developing cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

New Evidence: Mild AFP Elevation ≠ Fibrosis Progression

Emerging research over the last few years has challenged this blanket interpretation, especially in the context of mild AFP elevations (<~100 ng/mL) in HBeAg-negative patients. It turns out that AFP can rise for reasons other than tumor growth or fibrotic scarring – notably, from benign hepatocyte regeneration during liver injury. As one recent review pointed out, *“dramatic increases in AFP during acute or chronic hepatitis outbreaks may not be associated with tumors.”*In patients with cirrhosis who experience acute flares, AFP often spikes without any HCC developing pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. In other words, AFP is produced during active liver cell turnover (as in flares of hepatitis) and does not always portend malignancy or irreversible damage. This concept directly contradicts the older assumption that any AFP rise is dangerous.

Importantly, a 2023 study focusing on HBeAg-negative CHB patients provided a striking example. These patients were in the so-called “immune clearance” phase (active HBV replication with some liver inflammation). Paradoxically, those who developed AFP elevations during this phase actually had better short-term outcomes rather than worse. The study found that HBeAg-negative patients with rising AFP had a significantly higher likelihood of clearing HBV DNA, and the AFP increase had “no effect on patient prognosis” during the follow-up periodpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. In other words, in that cohort the AFP uptick was a byproduct of a robust immune response (damaged hepatocytes regenerating and secreting AFP) rather than a sign of impending fibrosis. The authors do note the follow-up was short, but this finding directly contradicted previous beliefs – showing that an AFP rise in such patients was not a harbinger of worsened fibrosis, but potentially a transient phenomenon with benign implicationspmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Inactive Carriers: Little to No Fibrosis Development

If your profile is that of an HBeAg-negative “inactive” HBV carrier – meaning normal or near-normal liver enzymes, low viral load, and only mildly elevated AFP – available evidence suggests your risk of progressive fibrosis is very low. Long-term studies of inactive carriers have consistently shown minimal fibrosis progression in these patients. For example, Tong et al. followed 146 HBeAg-negative patients (HBV DNA ≤10^4 IU/mL, persistently normal ALT) for an average of 8 years: none of them progressed to cirrhosis, and only 2 (≈1%) developed HCCeurjmedres.biomedcentral.com. Similarly, an Italian cohort (Bonacci et al.) reported that among a subset of “gray zone” CHB patients who were HBeAg-negative with low-level viral activity, not a single patient developed liver fibrosis or cirrhosis over a mean 8.2-year follow-up eurjmedres.biomedcentral.com. These outcomes highlight that people fitting this profile (“like you”) typically do not progress to advanced fibrosis in the long run. This favorable prognosis stands in stark contrast to earlier generalizations that HBeAg-negative status (often associated with a precore mutant virus) inevitably leads to worse liver outcomes. The key is whether you truly have low disease activity – if ALT is normal and HBV DNA is low, the liver is essentially quiescent, and fibrosis either remains stable or improves over time in most caseseurjmedres.biomedcentral.com.

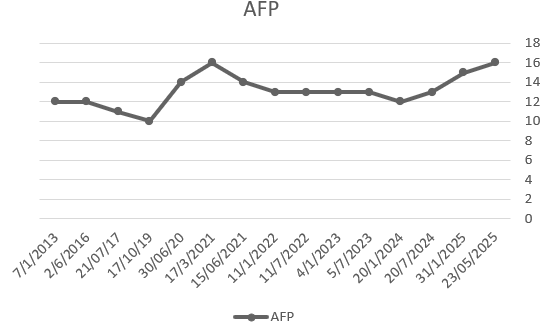

It’s worth noting that older studies didn’t always distinguish between truly inactive carriers and those with HBeAg-negative active hepatitis (which can feature fluctuating ALT and ongoing inflammation). In active disease, AFP tends to correlate with necroinflammation and fibrogenesis (as Uslu et al. found, linking AFP to “myofibrosis progression” in HBVpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). But in inactive carriers, a mildly elevated AFP by itself is often a red herring. One clinical commentary explicitly states that mild AFP elevations do not equate to presence of liver cancer, especially in the absence of other abnormal findingsdspace.library.uu.nljaypeedigital.com. The U.S. VA hepatitis guidelines similarly note that chronically mild AFP elevations are common in liver disease and should be interpreted cautiously, tracked over time rather than assumed to be cancer until proven otherwiselabanalyzer.orglabanalyzer.org. In practice, hepatologists have observed that some patients with chronic HBV have stable AFP in the 10–50 ng/mL range for years due to low-grade hepatic injury or regeneration – and if their scans (ultrasound/MRI) show no tumors and fibrosis tests remain normal, these AFP fluctuations are “false alarms” rather than indicators of undiagnosed cirrhosis.