Hi everyone! My name is Dong and I’m a PhD student under Thomas Tu. I’ve been working on understanding the consequences of HBV X protein (HBx) expression from HBV DNA integration, and its role in genomic instability.

More than 90% of HBV induced Hepatocellular Carcinomas (HCCs) contain multiple HBV integrations in contrast to 1 in 10,000 of the surrounding hepatocytes. This suggests a strong association between virus integration and HCC development, but we don’t know exactly how integrations cause cancer over decades of infection.

I’m interested in how HBx (the smallest HBV protein) is involved. It is usually really important for virus replication, but it can also affect DNA stability in the host cell.

When HBV DNA integrates into the host genome (as opposed to making cccDNA), bits of the virus DNA get chopped off. This means the integrated HBV cannot produce infectious virus and represent a replicative dead-end. It also means some bits of HBx are cut off, so it may not work or it works differently.

My job is to see if the HBx derived from integrations is functional and could contribute to cancer.

We have developed novel molecular tools to isolate, manipulate, and characterize cells containing HBV integrations. We generated over 100 cell clones with de novo integrations.

Under our model, we found integration junctions found that HBx regions required for DNA destabilisation were present in over 70% of integrations. We found that HBx expression from the integrations averaged ~4-fold lower than expression from cccDNA. We also found that at least some of the integrations were functional and that cells with existing integrations were 2-12 fold more susceptible to integrations after a new HBV infection (consistent with DNA instability).

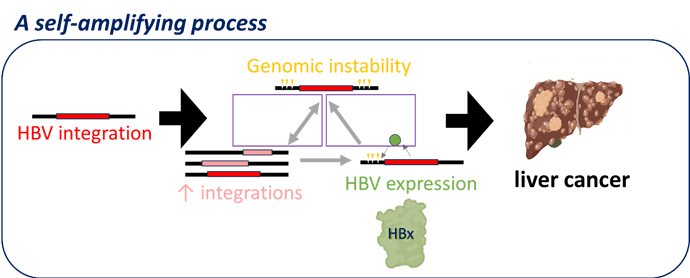

Figure 1: HBV integration promoting a self-amplifying process through HBx expression

So now we’re developing a new model of understanding liver cancer: we think that genomic instability is driven by virus integrations and that this instability leads to more integrations, promoting a self-amplifying process (Figure 1). The resultant exponential increasing genomic instability then fuels accelerated acquisition of cancer driver mutations.